SR#3 - State of 'Play' & 'View' : An Indian Test Cricket Fiasco

Reflections on ancient games and a billion dollar industry in the wake of Indian test cricket's biggest challenge yet...

Prelude

The past couple of months have been difficult as far as India’s test cricket is concerned. We’ve witnessed the team drop from towering success, down to the lowest of lows within mere days. Its sport after all.

Amidst this polarized spectrum of sporting prowess, we may have also witnessed the biggest divide yet between the ‘play’ and ‘view’. You see, antiquarian textual and material sources tell us that ancient games of Greece and other contemporary cultures were not modest. Held at monumental sporting spaces (stadia, colosseums), these games encapsulated a form of entertainment for spectators. With the evident patterns of what we observe today though, I wonder if ancient spectatorship connoted anything beyond entertainment. The element of contest or agon remains longstanding within these patterns. Even gambling has been evidenced from sources of the Greek antiquity and ancient China. While nascent games existed prior to the massive sports structures, there seems to be seldom knowledge about their nature. I suspect that the element of ‘view’ and ‘play’ both, were influenced by their socio-cultural contexts. Not unlike today.

This article will revisit the anthropological and sociological discourse on play and view in an effort to contextualize the current state of Indian Test Cricket and its viewership. Possibly the largest demographic in the sport. Read on…

‘View’ in Past Societies

The sporting structures belong to a period of complex social scenario. With established socio-political organization, trade, town-planning alongside underlying functions like hierarchies, belief systems etc.

The sporting events were governed by the rulers and kings, who perceived these violent contests as entertainment. One might point to specialized viewing areas for eminent figures of then-society found in the Harappan site of Juni Kuran in Gujarat dated to about five thousand years before now. The ‘view’ indeed, impacted structural aspects of the arena itself, with focus on the area where athletic events occurred if not performed. Effectively, a space dedicated to viewership with peculiar architecture consisting of radiating tiered seating areas and a central ‘playing field’ has remained constant throughout history.

Even with these structural patterns, the functional dynamics associated with them have been subject to transformation. If you consider the present as being a modern parallel of these patterns, the various eminent classes may have more high-stakes investments in these games. Perhaps in the context of socio-political outcomes if one chooses to deny an economic one.

Where ‘View’ and ‘Play’ Converge

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz penned the insightful Interpretation of Cultures (1973) and included the now-celebrated essay ‘Deep Play : Notes on the Balinese Cockfight’. The essay is a symbolic exploration of the said-game called ‘sabungan’, held in a 50 ft. arena called the wantilan or a cockpit where the genetically altered species of ‘gamecock’ make up the ‘play’ and a major part of the ‘view’ is dominated by a viewership of Balinese men.

However, it becomes apparent that underneath this illegal, cruel and religious sacrificial activity, is a representation of Balinese society at large. This is in simple terms, predicated by how much the ‘view’ is invested in the ‘play’. While the element of betting (toh) exists in the Balinese society with regard to cockfighting, the investment pointed at here is on a deeply symbolic and emotional level. Geertz writes about the men involved in the ‘view’ as not simply being the beneficiaries of the positive outcomes of these games but also as vehement exponents of this culture itself. Often, the birds are viewed as manifestation of power, strength and subsequent status of the men that breed, groom, train and feed them. The view here, allows for an intimate immersion into a form of activity that is in other cultures and societies, held at monumental venues with actual humans instead of birds. And yes, gladiators were captured slaves that fought in front of large crowds of people with varying degrees of invested interest in the games.

The element of ‘play’ in the Balinese cockfights belongs in the physical realm, to a set of designated species of birds but in some symbolic and sentimental sense to those that do not physically participate at all. A grossly unethical and unreasonable reality. However, these patterns of games are worth noting for how the sporting world continues to unfurl today.

The Billion-Dollar Cockfight

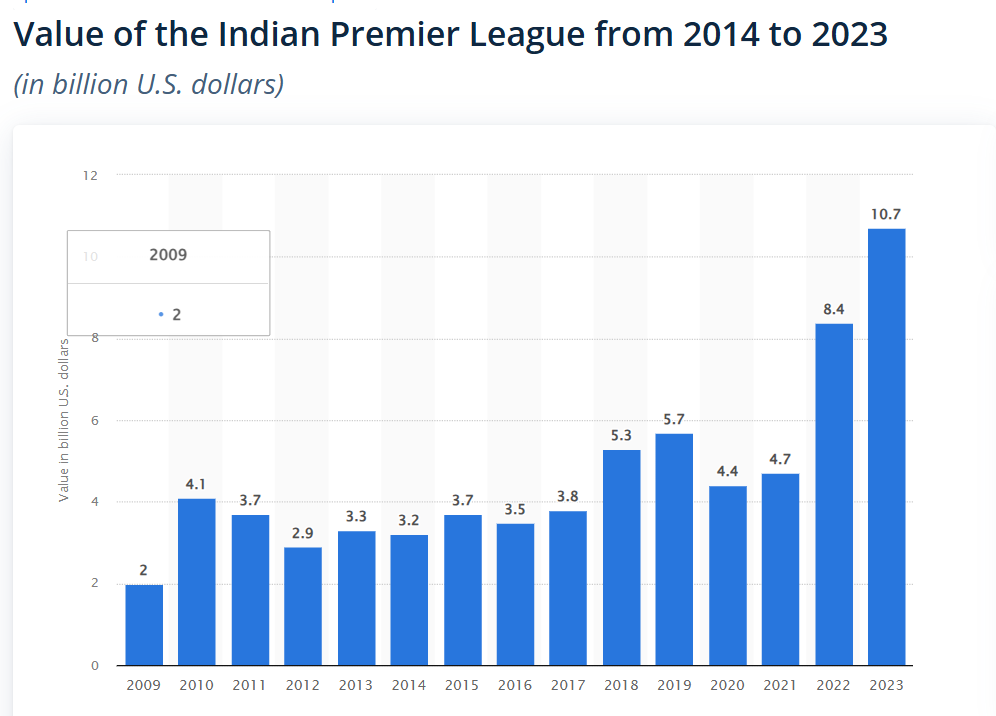

The world’s richest cricket board is the BCCI with a net worth of $2.25 billion and as a perspective, the not-so-close second is Cricket Australia with its $77 million. What encompasses the ‘view’ in such a colossal industry is everything from the spectators to the sponsors, administrators, franchise-personnel etc. This jacked-up cockfight (literally) paves way for young sportsman from far off towns to become sporting legends. However, the same has its perils.

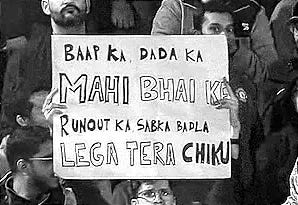

With the popularity of cricket and symbolism etched into teams/clubs, a modern parallel of the symbolic fanaticism of Balinese men is a form of hooliganism sitting behind the television set or on a smartphone. One can painfully remember how in 2021, Aussie all-rounder Dan Christian’s wife received rape threats on Instagram when he was unable to secure a victory for his IPL team - Royal Challengers Bangalore. But such is the double-edged sword, the big sporting industry. With heaps of sponsorships and media scrutiny, the everyday cricketer is not just a celebrity but in light of failure, a representation of the enslaved antiquarian gladiator. Your everyday fan, quite like the Balinese men, perceive athletes like Virat Kohli or Rohit Sharma to be an extension of their own strength and status. Akin to gamecocks in this billion dollar industry. Arguably, this stems from making the sport too intimate.

Television broadcasts and social media have turned every stadium in the world into a 50 ft. wantilan. The hooliganism too, is amplified in the form of hateful comments and threats on social media. The national athlete is a victim of every fan being under the impression that somehow, with the array of media-based immersions into the sporting world, they’re so symbolically invested in the athletes that a Return on Investment (ROI) is absolutely mandatory. In pursuit of this ROI, we see the ‘view’ impacting the ‘play’ in very negative ways.

India’s rare defeat against New Zealand, in their own backyard has thrown a light on how far this barbaric hooliganism has come. While the outcome was quite uncommon, its still sport with its fair share of uncertainty. The need for this emotional ROI has financial roots somewhere, either in its billions of dollars on sponsorship, broadcasting and on the players themselves. Regardless, a $2.25 billion dollar industry must not predicate sporting events upon having idealistic outcomes for starters. No, the average cricket fan did not groom, coach or feed the young Shubhman Gill or Yashasvi Jaiswal even though they’ve been under media scrutiny and the public eye since they were barely teenagers. With the sporting industry’s desire to bring the fan closer to athletes poses the risk of creating these exact misconceptions. And subsequent hooliganism.

The Culture Funnel of Sport

I’m working on the ‘funnel’ idea to see how cultural paradigms affect variability in art, sport, religion etc. to achieve a level of standardization (positive) or stagnation (negative). This will mark the first time I truly write these ideas for a public forum so I’ll avoid the theoretical ‘nerdy jargon’ and get to the point.

The sporting world is passing through a funnel of standardization with cricket being marketed to the baseball-dominated American demographic and LIV Golf’ ls use of Formula One-like shotgun starts or fast-paced broadcasts akin to cricket, football, motorsport and basketball.

It’s as if each sport is undergoing a negotiable alteration in terms of PR and marketing to arrive at a commonplace of acceptance from a broader demographic. This is the effort to have one fanbase bleed into another to assure viewership and revenue. That is why we see cricketer Jasprit Bumrah on the NFL YouTube channel teaching Micah Parsons how to bowl and football legend David Beckham attend a global cricket event. Its a steadfast attempt to have each sport become more relatable and accessible.

However, I perceive this as a mechanism to achieve surplus financial ROI at the behest of widespread symbolic ROI of sorts. If you have more people in the mix, you inevitably yield the former with the patterned market for the latter. This will bring problems and the abovementioned negative impacts. After all, the Balinese cockfighting events are rooted in subjective segregation that has strong cultural foundations. You can’t just conjure symbolism out of thin air.

I have reason to believe that there are factors beyond the media and PR that cause Americans to relate more to baseball and Indians to cricket. The inclination has historical bases, if not political causes. And with this ongoing standardization of sport, we’ll only reach stagnation. We’ll reverse to an era of enslaved athletes and corporations (unrelated entities) bigger than the sport itself.

Final Thoughts

The next two months are interesting. India will take on Australia in the 2024-25 Border Gavaskar Trophy, a much-awaited contest. These two teams have their own symbolic viewership, rooted firm in rivalry but also in nostalgia. Its good to see test cricket marketed the same way as T20 nowadays, a plus from the funnel that doesn’t bother me.

The IPL auction happens on 24th November which would put the big bucks in the spotlight again. Over forty-eight hours, nearly 574 cricketers will go under the hammer and a total purse of about 640 Cr. ($75 million) will seal the fates of everyone in the ‘play’ and the ‘view’. In the process, it will be decide who becomes the hype, the future and who dominates our television set during the next few years.

SportScape out!

Bibliography

[1] Charkiolakis, N. S. 2002. Ancient Greek Stadia. University Library Heidelberg.

[2] Christesen, P., & Stocking, C. H. (Eds.). (2022). A cultural history of sport in antiquity A cultural history of sport in antiquity. Bloomsbury Academic.

[3] Geertz, C. (1972). Deep Play. Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. Daedalus 101/1: 1-37.

[4] Hardy, S., Loy, J., & Booth, D. 2009. The Material Culture of Sport: Toward a Typology. Journal of Sport History, 36(1), 129–152.

[5] Pramanik, S. 2005. Excavations at Juni Kuran: 2003-04 A Preliminary Report, Purattatva 34:45-69

[6] Schofield, J. 2012. The archaeology of sport and pastimes. World Archaeology, 44(2), 171–174. doi:10.1080/00438243.2012.669603